Dateline: 1973 – 1974

The period from March, 1973 — August, 1974 was possibly the most important period of my life. On March 29, 1973, the last American troops left Vietnam.

The first time I remember hearing anything at all about Buddhism or Buddhists was when Thích Quảng Đức immolated himself on June 11, 1963. I was completing 3rd grade in Santa Maria, California. Pictures of him on fire were everywhere and it shook me deeply: I was, and continue to be, in awe of him. I’m not going to place any of the pictures here out of respect for him. His goal was achieved. I hope that I’ve met him in his new body.

On the same day, Vivian Malone and James A. Hood courageously walked into the University of Alabama after George Wallace was forced by the federalization of the National Guard to desegregate the school. On the next day, Medgar Evers was murdered in Jackson, Mississippi.

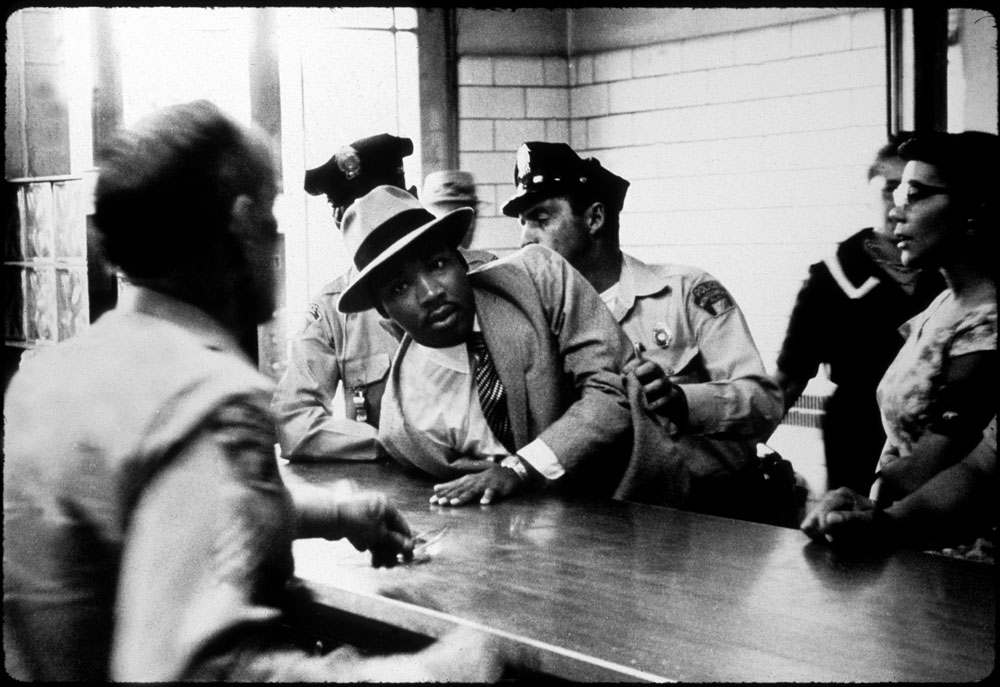

In April of 1964, when an all white jury refused to convict the murderer of Medgar Evers (later found guilty), our family moved to Huntsville, Alabama. On June 11, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was arrested in St. Augustine, Florida, for demanding service at an all white restaurant. In November he is denounced by J. Edgar Hoover, and in December is awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. I also knew nothing about these things at the time. We were busy driving across country singing, “I’m going to Alabama with a banjo on my knee.” in the car. But it wasn’t long after we arrived that we stopped singing. And over time Dr. King became one of the people for whom I had and have the deepest respect and gratitude. He brought more positive change to the world than it’s possible to quantify.

In August of the same year, the Gulf of Tonkin Incident was fabricated in order to justify 64 strike sorties of aircraft from American aircraft carriers and the escalation of the Vietnam War, then called a “police action”. The war was escalating and spinning out of control, and at that point I was attending 5th grade in Athens, Alabama, at yet another segregated school among narrow-minded, bible thumping, xenophobic white people who treated me as an alien. So, although I noticed it, the war was of secondary concern to me at the time. The Civil Rights Movement was being burned into my consciousness as my only internal defense against the backwater bigots who surrounded me.

In Huntsville, Alabama, my parents were required to buy my 4th grade school books even though I only attended for about a month there. The “history” book was called Know Alabama. It was the standard 4th Grade text book in Alabama from 1957 into the 1970s. It was written by close associates of George Wallace. I had it with me from 1964 until I gave it to Mrs. Brown, a teacher at Thousand Oaks High School who taught Black History, which I studied with her both in an elective class and as an independent studies student. Here’s the quotation I always remember as an epitome of my time in Alabama:

“They [the Ku Klux Klan] held their courts in the dark forests at night; they passed sentence on the criminals and they carried out the sentence. Sometimes the sentence would be to leave the state. After a while the Klan struck fear in the hearts of the “carpetbaggers” and other lawless men who had taken control of the state…. The Negroes who had been fooled by the false promises of the “carpetbaggers” decided to get themselves jobs and settle down to make an honest living.

We lived on six acres in the middle of an old cotton plantation. I enjoyed living in the country. My experience in suburban Santa Maria wasn’t pleasant, and it set the stage for my lifelong dislike of suburban life. In the country, after school when none of the bigots were around to harass me, I felt free and at ease. We had a barn and a machine shed plus a natural spring. There was a lot to explore.

And the highway, now Interstate 65, was being widened (probably as part of the slowly developing Interstate system, though that history is rather muddy). There was a huge billboard next to our property that read, “George Wallace is building this highway for you.” I never saw him out there, though. And I can’t find a picture of the billboard online. If you have one, I’d like to post it here.

The man across the dirt road was very old. His mother was a slave. He told me the first time I talked to him, “There are people who are niggers, and there are people who aren’t niggers, and it never has anything to do with the color of their skin.” He lived in a small, beautifully kept house. When mom and my brother and sister and I found a puff adder in our carport and thought we had stumbled onto a cobra, I ran to his house for help. He laughed and explained what a puff adder is and helped us put it out of our misery.

And Dad brewed beer at home in the prohibition County of Limestone, Alabama. He also made us go to Sunday School for the first and only time in our lives. I remember thinking, in fifth grade, how pathetic it was that they used grape juice for communion. Should anyone say, “that was good for you, it got you into church where you belonged,” my reply is, “it made me distrust Christianity as an organized religion in ways that I couldn’t possibly have mistrusted it before.” And I’m sure Mom and Dad only made us go because they were afraid that someone would burn a cross on our front yard if we didn’t.

The world was in turmoil. My world was in turmoil.

Then came the Battle of Ia Drang Valley, which began on October 19, 1965, my eleventh birthday, during the first half of sixth grade, as my time in Alabama drew slowly to a close.

I remember vividly that, after watching the above report by Walter Cronkite and Morley Safer on television with my parents in our house outside of Athens, Alabama, I began to cry. There was little doubt in my mind that my father would be drafted and sent to Vietnam and probably killed. He assured me that he had already served his time in the military and wouldn’t be drafted.

Although I was relieved that he would not be going to Vietnam my father had always worked long hours for IBM helping to build the guidance system for NASA’s Apollo Program. In that quest, we had followed the prototype around the country, beginning when we left our little house next to the creek on Long Creek Road, in Appalachian, New York, just before I began 1st grade in Alamogordo, New Mexico, near the White Sands Missile Range.

After my father worked with the rocket sled at White Sands, we moved on to Titusville, Florida, just across the Indian and Banana Rivers from Cape Canaveral; and next on to Santa Maria, California, near Vandenberg Air Force Base. Between these last two places, from 2nd to 4th grade, I saw more rockets launch than I could possibly count or remember. I also heard more details about nuclear power than most people would believe,

During the Cuban Missile Crisis, which began 3 days after my 8th birthday, on October 22, 1962, my father was considered to be essential personnel. He was sequestered in the rocket silo bomb shelters while the rest of his family lived next to a rocket base above ground. After that, he always carried guilt about it around with him. Guilt is a destructive emotion. It harmed both him and his family.

By the time my father worked on Wernher von Braun’s team at the Redstone Arsenal in Huntsville, Alabama, during the beginning of the Vietnam War and the height of the Civil Rights Movement,

I was already fully traumatized by visions of brutality, nuclear holocaust, and Cold War propaganda. I had a recurring dream of being taken away with my family in chains by the Russian Soviets to work in a forced labor camp. One summer evening, just before sunset, near the Cape, while I was swinging in the back yard, a rocket ascended and exploded in line with the sun. I’d seen plenty of rockets explode, but this time the entire sky lit up in Panavision multi-color because the explosion was back-lit by the sun. I believed that nuclear war had just begun. I was very sad, but didn’t believe it would help to run into the house. So just I kept going back and forth on the swing set and waited for the fire storm.

But, in early 1973, American involvement in the War in Vietnam finally came to a close.

Not much later, on May 18, 1973, the House Watergate Committee began nationally televised hearings. Then, on October 10, 1973, Spiro Agnew resigned, followed shortly by the “October Massacre” on October 20, 1973, the day after my 19th birthday.

The stage was set for my introduction to Buddhism.